Public media is under threat worldwide. From populism to funding concerns, the fight for public media was no better demonstrated than during the recent No Billag referendum in Switzerland. Here, the CEO of SRG SSR reveals all about the passionate campaign to keep the public licence fee and ensure the future of the country’s public broadcaster.

By Gilles Marchand, CEO SRG SSR

Normally when we think about Switzerland, a peaceful country in the centre of Europe, a number of images – or clichés – spring to mind. Such as mountains (the Matterhorn in Zermatt for those in the know), swiss cheese, and of course Roger Federer, the global hero, fantastic tennis player and model son-in-law… all we need to add is chocolate and banks and we’re good.

But this calm and tranquil country got fired up and torn apart for 6 months over this mysterious “No Billag” symbol.

This was a fight that rattled broadcasting organisations throughout Europe. “Billag” is the name of the company that collects the Swiss television licence fee. And It is expensive (CHF 365 from 2019) for 17 radios and 7 televisions in four languages. Yes, Switzerland is federal and complicated…

“No Billag” quite simply implied a total ban on all funding for the Swiss public broadcaster. This means SRG, but also 34 private radio stations and TV channels that benefit from 5% of the licence fee.

To understand that, we need to be familiar with Switzerland’s unique system of direct democracy.

Basically, since the second half of the 19thcentury, any citizen can put a constitutional change to a popular vote provided they manage to collect some valid signatures.

This is called the “federal popular initiative”. A citizen – or a party – can also challenge a law approved by Parliament in this way.

The 50,000 signatures initially required in the 19th century represented 8% of the electorate, while the 100,000 signatures required today represent less than 2% of the electorate….

Anyway, if the 100,000 signatures are collected, the government is obliged to put the initiative to a referendum within two years.

A discussion in a pub one evening…

In this case, the initiative against the television licence was launched by three young neoliberals following a discussion in a pub one evening. They explained that while they had nothing against SRG and its programmes, they could not tolerate being forced to pay a licence fee for TV and radio programmes that they didn’t watch. Their initiative called for a complete ban on all public financing, both direct and indirect. They explained that SRG’s productions were so good that they could easily be self-funded through pay-per-view and with more advertising.

They initially struggled to collect enough signatures. But they were joined and supported by a right-wing political party (Swiss People’s Party – SVP) and a professional association that campaigns against the licence fee imposed on companies. This financial and logistic support helped them easily reach the target number of signatures. Important to know is that the SVP Party is in fact Switzerland’s biggest political party with a share of more than 30% in the last federal elections.

Once the signatures were collected, Parliament scrutinised the initiative. Apart from the SVP, the Swiss parliament recommended rejecting the initiative, as did the Federal Council. And especially the communication Minister, very involved against the initiative. The SVP Party then proposed a consensus in the form of a counterproposal which aimed to reduce the licence fee by half. In exchange for this deal, the SVP would withdraw the initiative.

We fought against this consensus by trying to persuade Parliament to reject the proposal. And we won this first political battle. On the one hand, reducing funding by 50% would obviously have suffocated SRG. On the other hand, we thought it was a better idea to take a gamble and to ask the people for a clear and decisive decision – life or death for public service broadcasting.

“Take it or leave it!”

It has to be said that after the surprise anti-immigration vote in Switzerland in 2014, after the “Brexit”, and the election of Donald Trump, our strategy was considered somewhat risky… And with good reason!

What the polls were telling us in December 2017: 51% yes for the Initiative!

At the end of the year, the situation was very difficult. We weren’t allowed to campaign. Our employees, particularly journalists, were starting to feel very on edge, especially on social networks. They became increasingly aggressive and counterproductive.

At this point, the press was overwhelmingly against SRG. Publishers sensed a golden opportunity to see Switzerland’s main media group disappear, and was already looking forward to sharing out the remains, particularly in terms of advertising.

We were in the midst of our very own disaster movie…

We know the happy end – the horror film turned into a feel-good movie in the space of three months with a 71,6% against the initiative!

This was not entirely down to chance. Quite a lot happened in those three months

Firstly, we were very quick to get organised.

We set up a small national team, which I led with my deputy, consisting of the Head of Public Affairs, the Head of Media, the Secretary General of SRG, and the Director of Internal and External Communications. This very solid team was online 24/7 to coordinate all the actions and messages.

“This very solid team was online 24/7 to coordinate all the actions and messages”

We then involved the directors of SRG’s regional units by giving them a degree of autonomy within the established general framework. Only the political measures were exclusively managed at national level.

Then, in line with Switzerland’s good old federal tradition, independent committees were set up in each language region. These cross-party committees were allowed to campaign and raise funds. A national political committee, which brought together all the parties except the right-wing Swiss People’s Party, was also launched.

Finally, we mobilised the SRG associations in all languages and regions. It is made up of citizens, listeners and viewers who are committed to public service broadcasting. In a sense these members own the corporation as SRG is a non-profit organisation.

Once the structure was in place, we put out numerous clear and hard-hitting messages in our four languages. All the messages were underpinned by two powerful ideas:

The first was that there is no plan B. If you vote yes, it’s the end. The pay per view model is fanciful in a country with 8 million inhabitants split into four languages. Developing advertising is unrealistic in a saturated market. This seems simple now. But for three months, we didn’t budge an inch, although everyone (even our allies) were begging us to consider a plan B and make concessions.

The second core message was simple: without SRG, which reinvests in social and community projects in Switzerland, cultural diversity and Swiss identity would be jeopardised.

It should be pointed out that we have a very unusual equalisation system here in Switzerland: the German-speaking areas generate 73% of SRG revenues (advertising and licence fees) and retain 45%. The Italian-speaking region generates 4% and receives 22%. Meanwhile, the French-speaking part generates 23% and receives 32%.

The message was clear: with SRG there is no two-tiered media society. Everyone has the right to the same services, irrespective of the wealth and demographics of their region.

But such rational arguments were not enough because in the opposite camp, the populist messages were just as powerful:

Firstly from the neoliberals: “why do I have to pay for something I don’t use?”, “freedom equals choice”, “we can save hundreds of francs without noticing the difference as everything is online”, “TV and radio are dead”, “the licence fee is an unfair and outdated concept”…

And from the more populist conservatives:“why should we finance left-wing broadcasting?”, “Stop taxing companies”, “public institutions are too big and inefficient; we need to get rid of all these civil servants”…

And all of this was whipped up by the press.

Wake-up call: It’s about society !

So, in the space of a few weeks, the biggest wake-up call Switzerland has ever seen happened, with widespread mobilisation of civil society actors. This strategy was also somewhat risky. Because we knew that the mobilisation had to be widespread yet focused to be effective and turn the situation around. We approached tens of cultural, sporting and grassroots organisations from across Switzerland. We asked them to speak with their words and arguments. We documented them in detail in each sector. And then we took a step back. We didn’t really know how it would work out, apart from the fact that it would play out between 15 January and 15 February.

The wake-up call was launched in November, which was the most difficult time for us. And we waited until 15 January, leaving the communication channels to our opponents for two months. And that was a very long and nail-biting two months…

“The result was spectacular, marvellous and also quite moving”

The result was spectacular, marvellous and also quite moving. Tens of artists, comedians, sportspeople, councillors, YouTubers, influencers, teachers and many citizens… stepped up to the plate.

There were scores of clips and videos, thousands of messages on social media, hundreds of reader letters… Switzerland was overwhelmed by an extraordinary wave of cultural productivity. In all its languages. The response was so huge that we couldn’t even keep track of everything that was being produced all over the place, in a wave of spontaneous and staggering momentum. And from all sides a rallying cry of “no to No Billag”!

Meanwhile, our opponents weren’t able to show that a plan B was possible. Their arguments were easy to pull apart.

The wind changed at the end of January

During the last four weeks, our one obsession was to avoid a fatal error, to cover the campaign in a professional manner, to remain professional when responding to hundreds of questions and taking part in endless interviews. Not forgetting that we were constantly being observed and recorded. And that the slightest careless phrase would be seized on straight away.

“During the four-month campaign, there were 10,700 articles published in Switzerland (that’s around 50 a day!), hundreds abroad, 200’000 tweets and post”

And on 4 March 2018, public service broadcasting won. It was a great victory in all of Switzerland’s regions.

But we haven’t come out of this incredible battle unscathed. There are many lessons to be learned.

The legitimacy of public service broadcasting cannot be taken for granted. We have to secure it and be accountable. Performance is not enough. We mustn’t confuse market share (which is still very strong) with actual consumption (which is falling) and emotional connection. We can consume something without liking it.

The legitimacy of public service broadcasting cannot be taken for granted!

During this debate, we identified the following key points:

1 → The digitisation of society means people have a different relationship with media. Usage is fragmented, recorded, fickle. Linear consumption is crumbling, as is programme loyalty. Particularly for TV. This particularly applies to younger audiences.

2 → The value (price) of media is being questioned by the proliferation of free services. The television licence is considered too high. More and more people see this blanket mandatory fee as unjust and disputable. The payment method is also seen as archaic.

3 → The media ecosystem is in crisis. The business model of print journalism has been completely called into question. Advertising is flowing away from traditional media towards digital platforms. Journalism is not properly financed, and the situation is getting worse. Public service broadcasting is seen as too heavily funded and too powerful. The fight over allocation of public funds promises to be tough.

4 → The nature and scale of competition is changing. SRG faces competition from traditional rivals (foreign TV channels and radio stations, particularly French and German) and new ones (international digital platforms). The impact of these rivals is twofold: on the one hand, they take up a large portion of the available media time, and on the other they capture a large share of TV advertising.

In Switzerland, foreign stations have a 65% audience share, and 50% of TV advertising watched in Switzerland is on a foreign TV station. This trend is set to intensify as more and better digital offerings are developed. In the long term, it is going to be increasingly difficult to maintain linear audiences (TV and radio) and advertising revenues.

5 → Political support for public service broadcasting is more fragile. On the centre-right, on the right, but also, for other reasons, on the left.

6 → The gap between the people and institutions, which we are seeing everywhere is a major risk for public service media, as they are institutions that are (still) supported by national institutions.

7 → PSM’s attitude, but also that of its companies and employees is considered, rightly or wrongly, as self-satisfied, insensitive, sometimes arrogant. There was a widespread desire across the country to teach them a lesson.

Lessons learned…

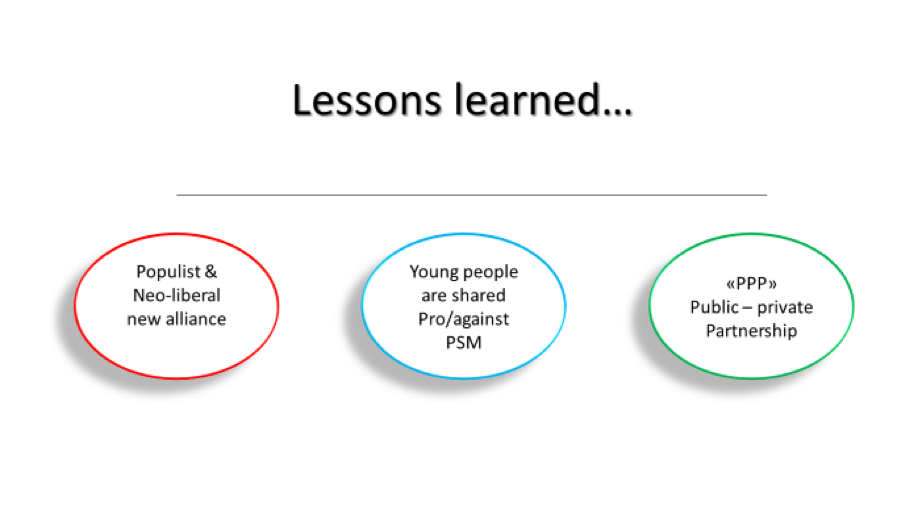

On the political front, there is an unlikely and dangerous new alliance which brings together neoliberal movements, libertarians and populist movements. The populists use the neoliberals to lend their conservative ideas a trendy and modern veneer.

The neoliberals use the populists to make more of an impact and become more effective on the political scene. And both are united against public service broadcasting.

On the generational front, there is some good news: not all young people are indifferent to public service broadcasting and the values it embodies. In actual fact, the fight was balanced in Switzerland. There were as many young people supporting us as opposing us.

“Not all young people are indifferent to public service broadcasting and the values it embodies”

On the market front, public service broadcasting can’t stay alone in a media desert. It would be too exposed. It needs to play a useful role in its ecosystem and one way or another seek out partnerships with print journalism and private sector actors, starting with independent producers. To my mind, the age when public service broadcasting thought it could do everything on its own autonomously is over.

On 4 March, as soon as we found out the results, we immediately set a date and announced changes. We wanted to take the initiative and not get tied up in the political agenda.

We decided not to trumpet our victory. Instead, we adopted a very restrained attitude and announced three movements:

- More efficiency to cope with the reduction and cap on our funds (around 8%)

- More differentiation with commercial channels to boost legitimacy

- More public/private cooperation to strengthen the national media

It won’t be easy. Other issues will arise, particularly within the organisation. But we have won the right to reinvent a future for Swiss public service broadcasting.

And for that alone, this is a venture worth undertaking…

Gilles Marchand is the CEO of SRG SSR, The Swiss Broadcasting Corporation.

Header Image: SRG-SSR building in Zurich. Credit: Roland zh/Creative Commons

Related Posts

2nd March 2018

Battered but not Broken | Why we need public media in the digital age

Public Media Alliance CEO, Sally-Ann…

19th January 2018

Insight | How public media should respond to journalism’s crisis

PMA President and Radio New Zealand CEO…